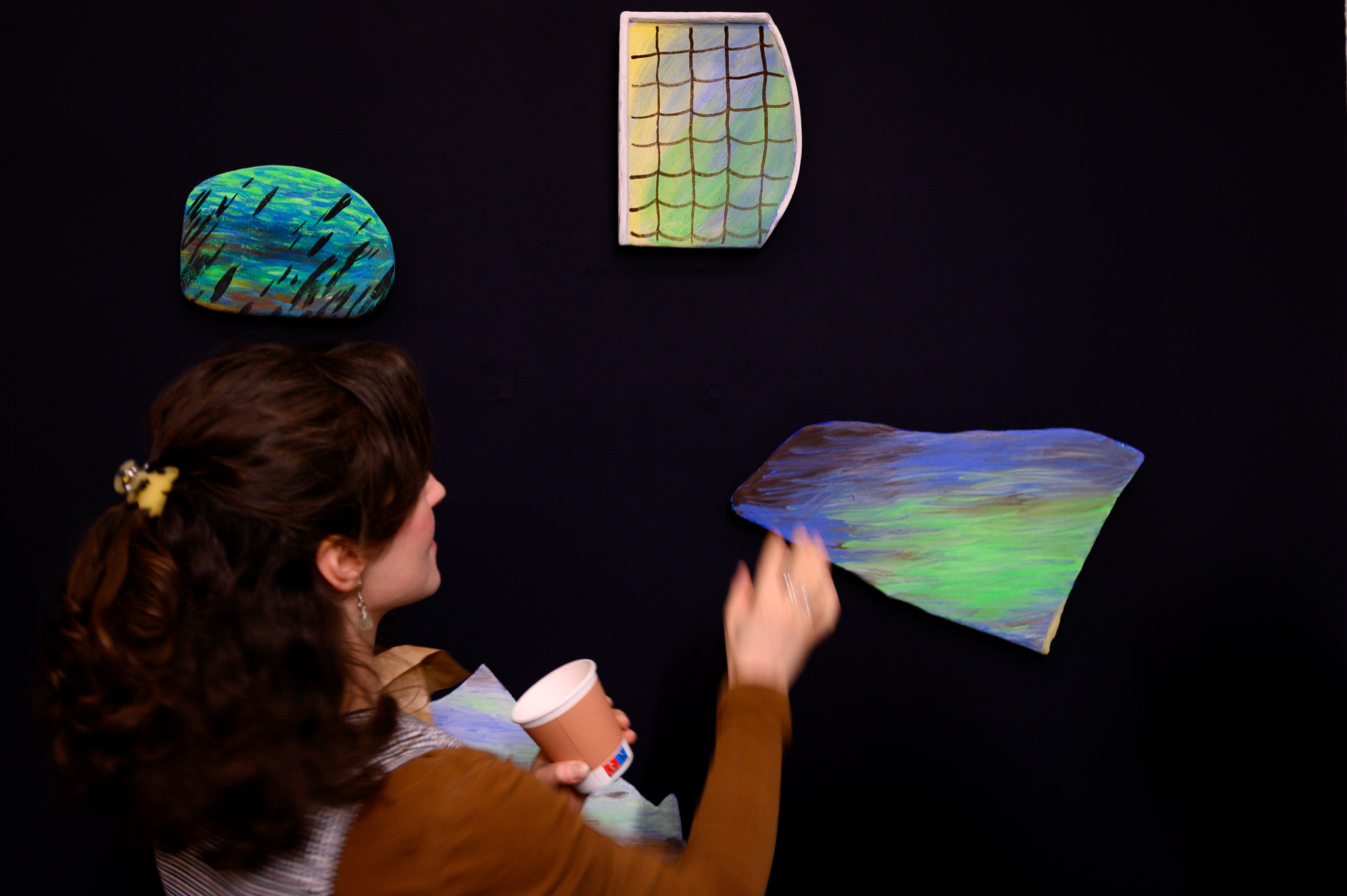

Photography of exhibition: Laura Gaiger

Photography of opening night (last 9 images): Martin Koch

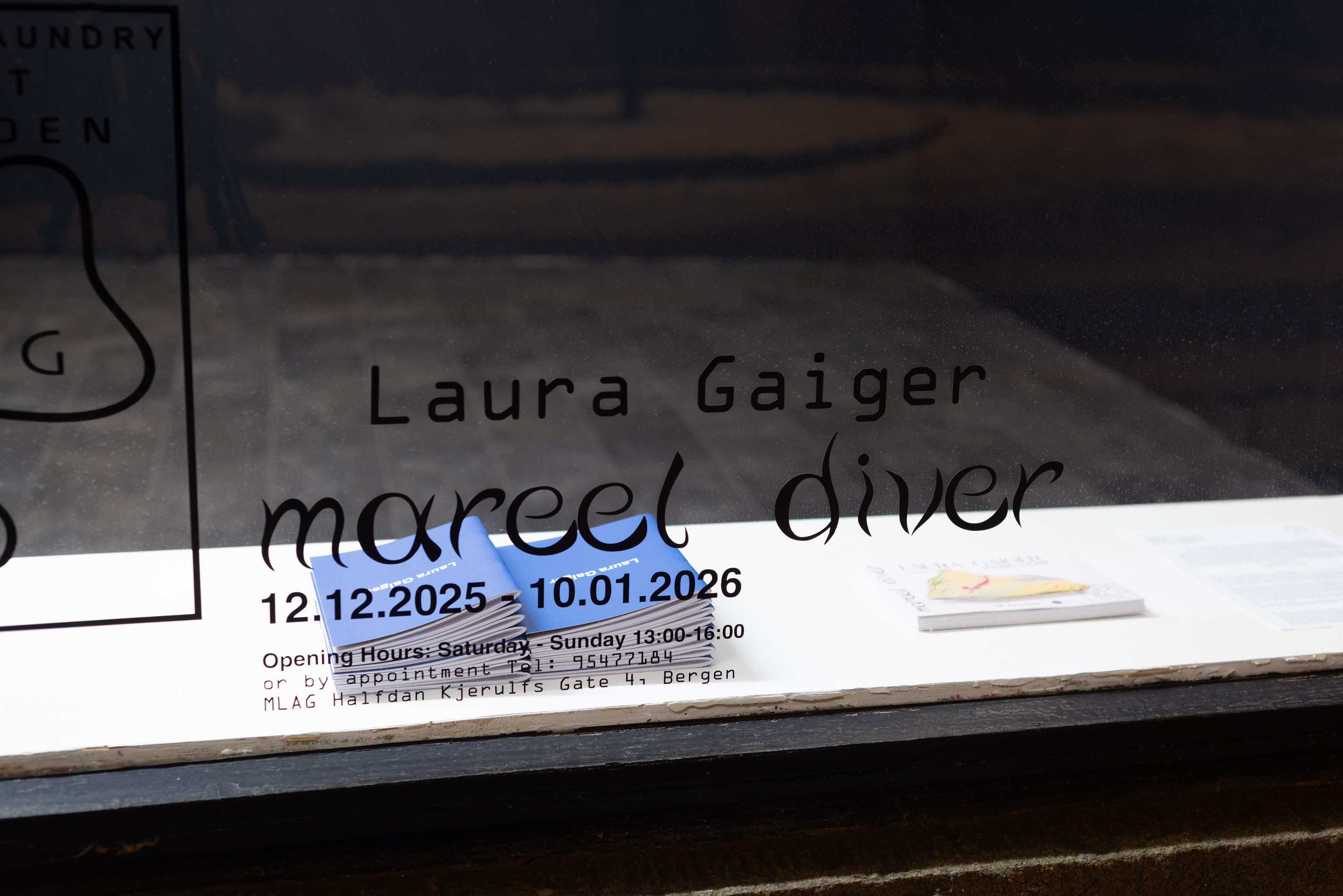

‘Mareel Diver’

exhibition text by Laura GaigerPart I: lime.

Lime is a strange material: liquid rock, limestone in limbo. Limestone and its sister rocks chalk and marble are calcium carbonate, the deposits of trillions of marine creatures over millennia, risen up from the sea into earth. It’s fitting for me, especially, that this rock is made from the sea: I can sit here in my floating home and think of minuscule creatures swimming beneath me, drifting slowly to their still beds, to become the foodstuff of rocks. I grew up on a raft of chalk which stretches across the Southern part of England and over France. This chalk, the softest form of limestone, was a part of life there: around the faucets, in the garden soil, floating as brittle flakes on top of a cup of tea. My family lived in a cottage called Chalky Down, on a farm named after a chalk pit. The more I follow the calcium carbonate, break it down, the more it shows up everywhere, like a kind of magic. The chalk has found its way into me, minerals absorbed by my body through water for 18 years, the landscape claiming me for itself. I wonder if, after so many years away from home, I still carry any of that chalk with me in my bones.

When you make a fresco you paint into liquid rock, and in minutes or hours it solidifies, painting turned to stone.

So to make a fresco one must embed pigment particles into fresh lime plaster, which become locked into the mineral structure when the plaster carbonises. This completes the cycle of lime: first a limestone rock, it has been heated (historically in a lime pit) until it decomposed into calcium oxide, known as hot lime, quicklime, caustic lime, or burnt lime - and CO₂ (stage 1). Then this calcium oxide, a white powder, was slaked. Water was added and a furious reaction occurred, producing liquid rock (stage 2). That was mixed with sand, drawn from a river, to make plaster. The lime plaster carbonised in the air and turned back into limestone (stage 3), but not before pigment was trapped inside. A painting turned to stone.

The lime cycle

Stage 1: CaCO₃ + heat => CaO + CO₂

Stage 2: CaO + H₂O => Ca(OH)₂

Stage 3: Ca(OH)₂ + CO₂ => CaCO₃

Stage 1: CaCO₃ + heat => CaO + CO₂

Stage 2: CaO + H₂O => Ca(OH)₂

Stage 3: Ca(OH)₂ + CO₂ => CaCO₃

Part 2: sailor

Soon I’m leaving, or at least I’ve been planning and dreaming of going away for a long time in my boat. Becoming a real sailor, finally. I could tell you I’m called to the seas, but aren’t we all?

Water covers two-thirds of the earth. It is hostile to human survival, but like all mammals, we enter this world through a miniature ocean. In a vestige of our aquatic evolutionary history, human foetuses are gestated underwater, in salty amniotic fluid, an enclosed sea we can inhabit just briefly, before we become truly mammalian at birth. Some people find their way back to the sea. Some return to it for pragmatic reasons, some to work, and some for escape, because the ocean eschews class and categorisation: it is as much an adventure playground for the rich and restless as it is a refuge for the desperate, the disenchanted and the indebted. Its cleansing salts bless all, its currents wear away all kinds of stains. I can sympathise with the pirates, with the Old Man, even with Ahab.

I am in love with sailors and sea stories, which by tradition are never wholly true. I am in love with the symbols of the sea, the white whales and the forty fathoms and the ways seafaring is woven into language like a secret code. And with the constant presence of life on boats: the way mooring lines can glow blue-green with bioluminescence when pulled from the water at night, or halyards whistle like banshees and thrum against the mast while I try to sleep. In winter I wake up at dawn to the sound of fifty eider ducks delving under the boat and pummelling the hull for barnacles to nibble on. It sounds like the water all around me is boiling. In the summer the eider ducks (norsk: ærfugler) leave, and the mackerel begin to break the surface with loud, sudden jumps and splashes, limbless and haphazard. Cormorants show up and dive for them. We slip loose the painter* and cruise around in the tender, eating ice cream and watching . I can come home from work at the art academy by boat across Store Lungegårdsvannet to Puddefjorden; I almost don’t need to be on land at all.

Last summer I sailed across the North Sea to Shetland, first time I’d been back to Scotland in seven years. I met an old friend for a drink and we talked about mareel (Shetland Scots), morild (norsk), noctiluca scintillans. Then I sailed back to Bergen and for the first time the algae showed up here, like it had overheard. Mareel surrounded the harbour in Solheimsviken, a thick orange soup by day

and an otherworldly radiance by night. The bioluminescence made me cry. It was so effortless and so spectacular, and watching it was more satisfying than looking at anything I’ve ever made in the studio. I didn’t dive into it, but I wish I had done. I just stood there with a stick, agitating it, making it light up, feeling better.

Part 3: diver

The obsession with the sea shared by so many - we come from it, we gestate in it, we live beside it, we go to it - goes back a long way, and I find this comforting. The Tomb of the Diver is a rare early fresco work, from around 470BCE, made in a city called Poseidonia. The enduring mystery of the painted tomb is its ceiling, where the fresco painting depicts a young man diving into waves from a ladder-like structure. He is alone, suspended in mid-leap, wide eyed and decisive, in contrast to the reclining groups of friends and lovers painted on the walls below. The painting is a mystery; nobody knows why there is a painting of a diver on the ceiling of a tomb containing a young corpse, and few paintings survive from this time period. The Ancient Greeks related diving to death, to the unknown, and especially to passion and heartbreak, so the diver has often been seen as a representation of the last spectacular leap into the void. He embraces it, he faces it head on, and this one glorious moment is preserved forever in lime.

When I started to look at images of the Tomb of the Diver and think about it, I didn’t know about the connection to Paul Thek. But after Michael mentioned it to me, I looked it up and noticed a couple of things. One of Thek’s small late blue paintings has a rendition of the diver that is so similar to the ancient one in the Tomb that I think there’s no question regarding its inspiration. And his is also reddish, but the head is tucked anonymously between the arms rather than looking triumphantly toward the water. I wonder if Thek was also thinking about death and the diver as a traveller between this life and whatever is beyond it, a traveller with Charon over Acheron and Styx to the afterlife.

The ancient diver is ecstatic, confident, and fully committed to this transition. I wonder if this is what drew Thek to the image, as it does for me? I love divers. I love birds that dive and people that dive. I like to watch them. One hot hot day this summer, close to midnight a group of young boys climbed up on the bridge over the harbour and dove from it, silhouetted against the red western horizon. One by one they soared down. I’m always cheering on Mathias leaping from diving boards or taking a sprint towards the waters’ edge, because when he’s suspended for a second mid-air, long limbs pulling the air into place as he drops and rotates to go fingertips first into the water, he’s a vision of fearlessness. When I dive, I stand close to the water’s edge. I spring cautiously forward, mostly dropping like discarded catch and sliding quietly under. But Mathias makes it a spectacle, arms and legs bent like an ungainly airborne frog before his body resolves into a harpoon. It’s ok to be a painter. Sometimes I wish I was a diver.

*In sailing terms, the tender is the small inflatable boat carried with a sailboat for reaching shallow waters. The line used to attach the tender to the sailboat is called a painter.